Kate Kinsella advocates the use of narrow reading units as a portal to word knowledge and literate discourse

I provide consultancy and professional development for districts across the nation that are striving to support English learners and under-resourced students in making viable academic language and literacy advances. I am observing with increasing concern as well-intended English language arts educators in grades 4-12 cobble together units of study in hopes of addressing the complex demands of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS, 2010) in time for the impending doom of the proverbial “cart before the horse” assessment debacle. Their legacy curriculum was not created to mentor English acolytes in systematic analysis of content-rich nonfiction, a range of rigorous text-reliant discussions using academic register, and argumentative writing drawing from multiple sources, all major emphases in the CCSS shifts.

With Next Generation assessments looming on the horizon, earnest English language arts educators are therefore teaching five days a week while also scrambling to locate appropriate reading selections, write depth-of-knowledge questions, and create text-dependent writing prompts and anchor papers — essentially building the airplane while they fly it — with scant time for reflection on pedagogy or revision of materials. I am routinely asked to review and bless ill-fated thematic units, compiled in lieu of an adopted and classroom-tested CCSS-aligned curriculum. Theme-based units have for decades been the curricular mainstay of elementary and secondary English language arts. While there are intuitive and evidence-based justifications for organizing upper-grades reading and writing coursework around unifying themes, the traditional approach to literary thematic unit development warrants reconsideration in light of the close informational reading and data-driven response demands posed by the CCSS shifts.

Legacy and Limitations of Literary Thematic Units

There are many reasonable arguments for orchestrating an English reading and writing curriculum around macro themes such as coming of age, developing friendships, overcoming obstacles, and seeking justice. Thematic unit education builds foundational background knowledge and fosters students’ connections to the real world (Morrow, L.M., et al, 1997). Universal human topics anchored by big-idea questions additionally enable students with diverse linguistic heritages and literacy skills to relate to issues and explore concepts in greater depth, rather than largely pursuing the right answer to questions regarding theme, plot, and character development (Garcia, 1993; Wiggins & McTighe, 2006).

Typically, a thematic approach to unit development within an English-language or reading-support course begins by identifying an age-appropriate theme reflecting a particular standards-based focus, student interests, challenges, and aspirations. After determining the direction and intent of the unit, language arts colleagues turn their attention to culling a number of literary selections that relate to that theme and lend themselves to application of focal standards, close reading, group discussion, and constructed response. For example, adolescent readers might delve into the universal theme of the forcefulness of love by initially exploring Shakespeare’s play Romeo and Juliet, followed by Lord Byron’s iconic poem “She Walks in Beauty,” and culminating with Taylor Swift’s chart-topping teen romance anthem “Love Story.”

Occasionally, an English language and literacy mentor might complement this literary suite with a news article featuring a contemporary Romeo and Juliet from rival urban gangs forging cultural and romantic bridges. Many English learners and striving readers will, no doubt, find the brief foray into pop music and current events a welcome respite from weeks of meticulous literary analysis. However, these addendums to the core narrative selections are often cursory and have little bearing on a culminating assessment or benchmark essay prompt. In most concept-driven units found in English language arts coursework, nonfiction selections are omitted entirely or added as something of an afterthought, with the central literary works earning weeks of carefully mediated in-class reading, analysis, discussion, and related writing.

While the teacher may devote several lessons to dive deeply into the nuances of the generational mother-daughter conflict in the Joy Luck Club or the animal imagery in Beloved, vocabulary analysis is often limited to enigmatic or artistic word play within passages. Point-of-use explications or guessing meaning from context clues is largely focused on “stumblers,” low-incidence vocabulary words that have little bearing on the focal concepts, character evolution, or plot twists. Curriculum developers rarely provide educators with a relevant lexical and syntactic toolkit to assist academic English learners in competently exploring the narrative themes. Words briefly glossed in the margins of narrative passages and those included in the end-of-unit vocabulary bank generally amount to a lexical fast food diet. Esoteric or arcane words like “ebullient” and “periphrasis” have little bearing on text comprehension and the challenging collaborative and independent tasks students are assigned. Diffident readers and academic English learners thus approach Socratic seminars, small-group discussions, and culminating essay assignments with a tenuous grasp on the theme and anemic vocabulary to articulate their understandings. In a literary thematic unit on development of identity, students might read a poem, a short story, and a scene from a play, none of which include the specific vocabulary students will require to adeptly respond with lexical precision related to that theme.

In English support classes, reluctant readers, including English learners and native English speakers, may have more regular ventures into informational text study. However, the selections assigned to basic readers are characteristically brief and laden with highly decodable words, at the expense of more engaging and relevant issues and portable, high-utility academic vocabulary. Further, the fluency passages developing readers consume over the course of a week often amount to an attention-deficit unit, with the genesis of the American potato chip on Monday, the ruins of Pompeii on Tuesday, and the idiosyncratic eating habits of koala bears on Wednesday. Basic readers never attend to any topic long enough to develop conceptual and lexical foundations that would enable them to tackle a more challenging related text and writing task with greater odds. Of equal concern, students in reading-support coursework are apt to be assigned different texts based on assessed or perceived skill deficits, so they squander vital class time silently completing worksheets with entry-level comprehension questions rather than engaging in thought-provoking interaction with peers and text-dependent written response.

Increased Percentage of Nonfiction

The major CCSS shift toward inclusion of frequent and varied nonfiction reading and response calls for a serious reconsideration of the unrivaled status granted to literary thematic units in upper-grade English language arts, English as a second language, and reading coursework. The CCSS aim to align instruction with the National Assessment of Educational Progress framework. As such, there are the same number of standards for literature and informational text in all grades, with informational text analysis and response receiving more weight and frequency as students progress through upper-elementary and secondary levels. Issue-based informational texts thus warrant equal attention, rather than a tertiary role, to help develop the advanced English language, literacy, and communication skills all students need to participate fully in American schools, workplaces, and society.

In light of the Common Core call for an increased percentage of content-rich nonfiction in grades 4-12, it makes sense to consider frequent and productive ways to devote students’ attention to issue-based articles, essays, and reports in English language development coursework. Tagging a brief nonfiction selection onto the end of a lengthy literary thematic unit does not provide adequate practice within standards addressing synthesis of significant content from varied sources, formulation of a position, and constructed verbal and written response.

Complementing with Narrow Nonfiction Units

An efficient way to integrate more stimulating informational text analysis while mirroring the real reading demands of college and the workplace is to create “narrow reading” units of study. Krashen (2004) defines narrow reading as reading several texts by “one author or about a single topic of interest.” Krashen describes various ways second-language students can gain multiple exposures to new language structures and words in a comprehensible context through narrow reading of books, from devouring a children’s series like the Magic Tree House to drilling down on a novelist like John Grisham’s favorite expressions and distinctive style. Krashen also advocates inclusion of narrow reading units built upon a current event addressed in news media.

There are two key approaches to crafting a narrow reading unit that make the most sense within an upper-elementary or secondary course focused on advancing English language and literacy for academic success. One form of narrow reading guides students in reading daily newspaper accounts of an ongoing story, such as the March 2014 Malaysia Airlines flight that vanished. Another type of narrow reading consists of relatively brief but increasingly complex and varied informational texts that concentrate on a specific subject or issue, for example, the role of grit in high achievement.

Where Narrow Reading and Thematic Reading Differ

Narrow reading units differ markedly from literary thematic units in that each selection addresses the same topic but from a different vantage point and in greater detail. In narrow reading units, critical background information is typically recycled before new developments, insights, and evidence are introduced. As an illustration, in a narrow reading unit focused on Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, an initial news story would provide basic facts regarding the missing aircraft, from the time of its disappearance after takeoff in Kuala Lumpur and its intended destination to the number of crew members and passengers. Subsequent online or print news stories would revisit aviation-incident essentials and recent developments before segueing into new facets of the search-and-rescue efforts, investigation hypotheses, and the international response.

Narrow reading units more closely mirror the complexities of college-level course assignments than thematic units in that advanced study requires tackling a number of texts on a specific topic from varied sources. A literary thematic unit is loosely connected around a central concept like “equality” or a somewhat elusive question like “What is the best way to find the truth?” In contrast, a narrow reading unit uses multiple texts to delve deeply into a relevant issue, such as the increase in cyber bullying amongst adolescents or the demand for “soft skills” in the contemporary professional workplace.

Lexical Merits of Narrow Reading

One of the agreed attributes of narrow reading for academic English learners is the predictable recycling of key concepts and related high-utility words and phrases, consolidating students’ background knowledge while increasing receptive word knowledge (Krashen, 2004; Schmitt & Carter, 2000). Reading on one specific subject means that much of the topic-focused vocabulary will be repeated across texts, which facilitates the reading process and affords the reader a better chance of comprehending and learning the vocabulary. It is challenging for neophyte academic-English speakers to comprehend reading content and free up brain trust to learn new words within complex text when they are continually bombarded with foreign concepts, sophisticated sentence structures, and novel vocabulary they can neither pronounce nor recognize.

Schmitt (2000) points out that vocabulary uptake from reading a single brief text is actually quite small and that it is only through repeated exposures from a considerable amount of focused reading that an array of new words is gleaned. Research supports this premise, showing that the probability of learning a new and challenging term from a single meeting in context is, unfortunately, extremely low, varying between 5% and 14% for both native English speakers and English learners (Beck et al, 2002). The word-level skill to successfully exploit partial meaning from context before verifying meaning in a dictionary is a crucial academic competency. However, context analysis should never be utilized as the primary or sole instructional strategy for building vocabulary knowledge, since research illustrates that it is a protracted and often fruitless endeavor.

Reading successive texts on a specific topic makes certain words far more salient and consolidates a word’s meaning in the learner’s mind (Schmitt & Carter, 2000). Narrow reading also supplies the varied contexts necessary for an academic English scholar to gain an appreciation of the true range of a word’s meaning (Nation, 1990; Schmitt & Carter, 2000). This vocabulary repetition in rich informational contexts better equips students for collaborative conversations and constructed-response tasks requiring literate thinking and academic register. In sum, the case for narrow reading as a powerful vocabulary-acquisition device is very strong.

This brief excerpt illustrates the lexical density and precision of authentic, complex informational texts. Unlike literary selections, authentic informational texts tend to utilize vocabulary one needs to engage in competent academic communication about the topic; by contrast the requisite vocabulary for discussion of literary themes and developments is typically located in the related discussion questions and writing prompts, not the actual narrative passages. Words written in upper case are directly related to the central topic, the merits of being bilingual, while those highlighted in bold face are not topic centric but are high-utility academic words that serve as the linguistic mortar in this investigation.

In this day and age of increasing GLOBAL interconnectivity, having the ability to speak more than one language is a highly VALUED skill. Studying a foreign language is a requirement in some schools in the United States, but in some countries, it’s the law that all students pass two languages before they are allowed to graduate. Meanwhile, those who grew up learning only English are taking language classes in droves. There is a reason, of course. BILINGUALISM can very well translate to better job opportunities and better pay. In some career paths, FLUENCY in more than one language is an absolute requirement.

Source: “The Effects of a Second Language on the Brain.” Pinantoan, A. (2012, July 21). Retrieved from http://www.cerebralhacks.com/

brain-exercises/the-effect-of-a-second-language-on-the-brain.

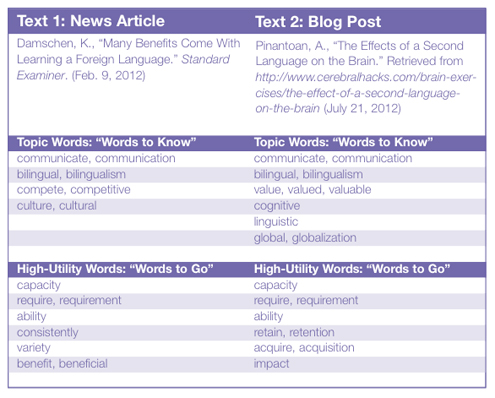

The table below (Figure 1) compares topic-centric “words to know” and high-utility “words to go” in two informational texts comprising a narrow reading unit I developed to guide adolescent English learners in exploring the social, professional, and academic merits of mastering an additional language. As the table illustrates, there are recursive topic-centric terms across the two texts, a feature news article and a blog post, including communicate, communication, bilingual, and bilingualism. Each text contains additional valuable terms for articulate class debate and written response, ranging from cultural to cognitive and linguistic. Note as well the highly portable and practical words addressed in the two texts, like capacity, requirement, impact and consistently, that will serve academic English learners well when articulating their understandings of this unit focus and lessons across the disciplines.

Building a Narrow Reading Unit

I have extensive experience collaborating with colleagues to craft narrow reading units as curricular anchors in English courses for students at various levels of second-language proficiency, in elementary, secondary, and college contexts. The first step is identifying cognitively dignifying topics that would be appropriate for the age and academic context. I also strive to distinguish between my current cause celèbre and relevant topics that would hold my students’ interest. While I may wish to share my exuberance for Carol Dweck’s research on growth mindset at the onset of the school year, I have come to see the wisdom of offering my academic language acolytes an array of unit topics former secondary students have appreciated and allowing them to have some choice in our initial forays into close reading and collaborative conversations. Characteristically, they shy away from aspirational topics I might prefer and gravitate toward issues with immediate relevance to their personal lives, like the following: “teens behind the wheel,” “teens and money,” and “teens and social media.”

Once I have established a narrow reading focus, I search for an array of relevant texts and select a few (2-4) that build in complexity while recycling central concepts. I have learned the value in launching a unit with a relatively brief and accessible text that serves as a conceptual and linguistic cornerstone, introducing rudimentary information on the topic which students can leverage as they approach the subsequent text. Beginning with an interesting but exceptionally challenging text will surely backfire. With so much available online, it’s fairly easy to find a variety of texts for narrow reading units. Be careful, however, as they sometimes presume a fair amount of background knowledge and are written for a relatively sophisticated reader in agile, complex prose.

I have a number of print and digital sources from which I have reliably obtained excellent selections to initiate or delve deeper within a narrow reading unit. For upper-elementary students, I routinely draw from these sources for current, issues-based news articles written in engaging and accessible academic prose: Time for Kids, and Scholastic News. If I wish to focus on an environmental issue or science subject with elementary youths, I have found these sources of great value: National Geographic Kids, National Geographic Explorer and Ranger Rick. I look to a variety of sources for reliably well-written exposition on topics of interest to my secondary students. For current events, I regularly use articles from two excellent Scholastic News magazines: Scope (middle school) and Upfront (high school). I appreciate that neither of these current-events periodicals written for adolescent readers attempts to sound like teenagers, and instead they use articulate, well-organized academic prose, serving as models of the exposition and argumentative writing students are expected to produce in the Common Core era.

The periodicals I have turned to most regularly for quality, introductory nonfiction texts exploring a thought-provoking issue are written by a former English as a second language and history teacher, Lawrence Gable. Gable has been producing accessible informational texts about current national and international events for academic English learners for the past decade. He writes a monthly topical article for three original periodicals (www.whpubs.com): What’s Happening in California?, What’s Happening in the U.S.?, and What’s Happening in the World? In an article that spans approximately ten paragraphs on an 8” x 11” paper, Gable introduces a focal issue such as the rampant racism in world soccer in a detailed journalistic style, then provides related factors, developments, and food for thought, without interjecting his own biases. He provides subscribers with two versions of the same article at different reading-proficiency or Lexile levels, which has enabled me to offer a more appropriate reading task to any exceptional student with skills considerably lower or higher than the rest of the class.

Reader Stamina and Motivation with Narrow Reading

While the conceptual and lexical advantages of narrow reading for English learners are well documented (Cho, K.S., & Krashen, 1994; Schmitt & Carter, 2000), there are other equally compelling outcomes. In a traditional English language arts anthology or thematic unit, there will predictably be many selections of minimal interest and relevance to readers with weak academic-language skills and a less-than voracious reading habit. Krashen (2004) argues that the bombardment of new vocabulary, unfamiliar style, disconnected context, and lack of reader engagement ensures that much English language reading remains “an exercise in deliberate decoding.”

The following excerpt from a former tenth grade student’s learning journal is a testimony to the lack of confidence and competence many academic English learners experience with their core reading assignments. Stalled at intermediate English proficiency after six years in U.S. schools, Daniel’s compelling description of his arduous and demoralizing reading process speaks volumes about the need to create narrow reading units that build background, vocabulary knowledge, fluency, and confidence.

“Today is my sixth year that I am studying English as my second language. And I am still stuck in reading. I have had big conflicts with reading, and disappointment sometimes. I can see that I can communicate with others. I can see that I can talk to others. I am not afraid like I used to be. But when I am reading, it is different. I do usually understand when my teacher is talking. But when we get to the point that we have to read, I can read it, and I can pronunciate the words okay, but so many times I can’t really understand, and it’s because of the same thing. There are so many pages of new words. And ideas I don’t understand. And so I think reading is the hardest part in school for me. It’s very disappointing when I am reading and trying to understand all those new words. I have to go to the dictionary and look up the meaning of a new word, and a minute later I have to stop and look up another word, and then find the definition, and go back and try to figure out the main point. I do this over and over, and I still don’t really understand. And that’s a drag. It’s like a dream I have that one day I will read one book and understand it.”

Affording less-proficient readers and English speakers the opportunity to read consecutive selections on a topic of genuine interest and relevance will build crucial schema and fire dendrites during class discussions of text, a somewhat rare occurrence in many mixed-ability English classes. Students will be more willing to roll up their sleeves and tackle increasingly complex text if they perceive that they can be successful. Equipped with conceptual and lexical foundations gleaned through an accessible introductory informational text in a narrow reading unit, habitually less confident readers will be far more inclined to endure some cognitive dissonance and complete multiple reads of a subsequent, more ambitious text. Despite the Common Core rhetoric about building student resiliency with text, we are not apt to develop crucial mindsets and skill sets when students rarely feel successful or engaged with assigned reading material. Taking a break from arduous literary texts to explore a contemporary issue in detail will do much to re-engage students who have long perceived that they are the only ones who don’t grasp the irony in Shakespeare or the eloquence of Emily Dickenson.

References

Beck, I.L., McKeown, M.G, & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

Cho, K.S., & Krashen, S. (1994). Acquisition of vocabulary from the Sweet Valley Kids series. Journal of Reading 37: 662-667.

Common Core State Standards (2010). “Applications of Common Core State Standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects.” Retrieved from www.corestandards.org.

Garcia, E. (1993). “Project THEME: Collaboration for school improvement at the middle school for language-minority students.” In Proceedings of the Third National Research Symposium on Limited English Proficient Students: Focus on Middle and High School Issues (pp. 323-350). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Bilingual Education and Minority Language Affairs.

Hwang, K., & Nation, P. (1989). “Reducing the vocabulary load and encouraging vocabulary learning through reading newspapers.” Reading in a Foreign Language 6(1), 323-335.

Krashen, S. (2004). “The case for narrow reading.” Language Magazine, 3(5): 17-19.

Morrow, L.M., Pressley, M., Smith, J.K., & Smith, M. (1997). “The effects of a literature-based program integrated into literacy and science instruction with children from diverse backgrounds.” Reading Research Quarterly, 32(1), 54-76.

Schmitt, N. (2000). Vocabulary in language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Schmitt, N. & Carter, R. (2000). “The lexical advantages of narrow reading for second language learners.” TESOL Quarterly 1: 4-9.

Nation, I.S.P. (1990). Teaching and learning vocabulary. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2006). Understanding by Design. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Kate Kinsella, EdD (katek@sfsu.edu) is an adjunct faculty member in San Francisco State University’s Center for Teacher Efficacy. She provides consultancy to state departments of education throughout the U.S., school districts, and publishers on evidence-based instructional principles and practices to accelerate academic English acquisition for language-minority youths. Her numerous publications and programs focus on career and college readiness for academic English learners and under-resourced students, with an emphasis on high-utility vocabulary development, informational text reading and constructed response.