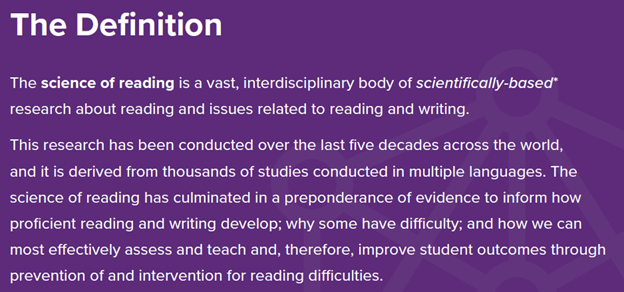

For at least a half-century, there has been a great deal of discussion about how children learn to read. While policymakers, curriculum developers, educational leaders, and those in the media have been using this discussion to drive headlines and policy, reading scientists across the world have been formulating questions and conducting experiments to find answers to specific questions regarding how the human brain learns to read. We are far from knowing all the answers, but the research does provide many important concrete understandings about how our brains acquire the complex process of turning marks on a page into language, as well as what to do when it has difficulty doing so. This vast, interdisciplinary body of scientifically based research, derived from thousands of studies conducted in multiple languages (see The Reading League, 2022, p. 6), is the science of reading (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

The Definition of the Science of Reading

For too many years, the science of reading accumulated in journals without benefiting those for whom it was developed—practitioners and students. Thankfully, it is now finally making its way into the work of educators and educational leaders, policymakers, and educator preparation programs and is sought by parents striving to find information on how to address their children’s reading difficulties. It is an exciting time for education, knowing that this research is finally being shared and used to build professional knowledge and guide practice in an effective way. Noticeable shifts are occurring across the country, even the world, and the positive data trends in schools that align their knowledge, materials, practices, and systems with the research of how students learn to read are causing many to take notice.

For some, however, the emergence of the science of reading seems like something new, and it brings uncertainty. Why are people using the word science along with reading? Do researchers know what it is like to be in a classroom? Why does a certain kind of research seem to be prioritized? Has this research included students exactly like mine? If not, can I trust it? And whom do I listen to? Confusion is leading to misunderstandings that have now become apparent in our national conversations. In 2021, a group of reading experts noticed misunderstanding arising and gathered to write the “Science of Reading: Defining Guide” (2022) to clarify the term the science of reading.

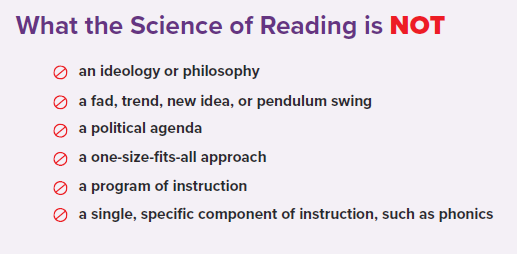

This resource provides a definition of what the science of reading is, what it is not (p. 9, see Figure 2), and how all stakeholders can understand its potential to transform reading instruction.

Figure 2

What the Science of Reading Is Not

Two of the most widespread misrepresentations about the science of reading from Figure 2 are described and clarified in the next two sections.

Misconception #1: The science of reading is a one-size-fits-all approach

When educators undergo training in the science of reading, they often learn about areas of the brain that are used for skillful reading. They learn that unlike neural circuitry that we are born with to process language, instruction is required to build the circuitry that evolves in order to learn to read words on the page. Research-validated frameworks are presented to show that reading comprehension cannot take place if there is a difficulty reading words automatically or comprehending the words once they are read. They also learn about the foundational skills of word recognition (e.g., phoneme awareness, phonics, decoding, encoding) and the subskills of language comprehension (e.g., vocabulary, background knowledge, syntax, semantics). A good training will also include an understanding of language including phonology, morphology, grammar, and the reasoning behind particular spelling conventions. In addition to building this professional knowledge, educators are often prepared to select and use valid assessment data in order to provide differentiated instruction according to student need. Overall, this training allows educators to understand and recognize the individual needs of their students—the antithesis of “one size fits all.”

The Reading League and friends were privileged to recently engage in a series of meetings with the National Committee for Effective Literacy (NCEL). During these discussions, several participants posited that this misconception of the science of reading as a one-size-fits-all approach likely stems from poor implementation of the findings from the science of reading. In efforts to “do the science of reading,” schools often neglect the critical first step of building professional knowledge through ongoing, expert professional development. Instead, they are often quick to respond to the lure of publishers who claim their curriculum “are” the science of reading. In reality, published materials for teaching reading may only support a specific subskill, and meanwhile uninformed decision makers in a school believe they have checked the “science of reading” box. The research behind how skilled reading develops cannot be found in a one-size-fits-all box or by simply buying a new program. Knowledgeable, trained decision makers and educators will know better than to implement a program without consideration of how reading develops and how to differentiate instruction. It is our hope that experts will converge in this understanding to address this widespread problem together.

Misconception #2: The science of reading is a single, specific component of instruction, such as phonics

There is no research or guidance to support the false claim that phonics is all a student needs to learn to read. There are several meta-analyses based on hundreds of scientifically based studies proving the essential nature of explicit phonics instruction in developing skilled reading. It is necessary, but not sufficient. In order to comprehend while reading, students must be able to connect the words, phrases, and texts to their meanings. Imagine, if you will, trying to read the entire alphabet as a word. We may have adequate decoding skills to stumble through it, but it will be meaningless.

There is a great deal of research from the science of reading that reveals the primary importance of building language comprehension to support reading comprehension. If reading is turning printed squiggles into speech, speech and language serve as anchors. This is done first through oral language as students acquire the ability to decode print, and later through both oral language development and learning through reading.

This discussion point is an important one to consider for English learners/emergent bilinguals (ELs/EBs). Many native-English-speaking children come to school with well-developed vocabularies. Emergent bilingual students who begin school in English-only settings also often come to school with well-developed vocabularies, although often not in the language of instruction.

It remains essential to build the same neural connections in their brains for decoding that all readers must build through explicit and systematic instruction in the subskills of word recognition. But this must be done with concurrent attention to building language comprehension, both in a student’s native language and in the language of instruction.

See The Reading League’s “Curriculum Evaluation Guidelines” (2022) for additional information on the evidence base for practices that support the development of both word recognition (decoding) and language comprehension.

The science of reading includes all learners

There is a long list of questions that have yet to be answered in reading research that is specifically related to populations of students such as ELs/EBs. For example, how do we best determine student need authentically if assessments are not available in their home language? What’s the most effective way to use contrastive analysis of a student’s home language and the language of instruction to expedite instruction and intervention? How can we ensure students are gleaning information from the text once they are able to accurately decode the words on the page?

However, claims that a separate research base apart from the science of reading is needed for this specific population of students are not factual. For instance, the “Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth” (August et al., 2009) has been identified as part of a research base that is separate from the research that comprises the science of reading. If we acknowledge that the science of reading refers to the research of how all humans learn to read, we can come to agree that any experimental (scientifically based) research cited within the Literacy Panel’s report is in actuality a part of the body of knowledge that is the science of reading (see “Defining Guide,” p. 11, for more information).

Similarly, claims that there is no scientifically based research related to ELs/EBs (i.e., conducted on monolingual students only) are untrue and serve only to call into question the research base that the science of reading draws from. An example of this is disregarding the research that the framework used to describe the reading process is built upon (see Hoover and Gough, 1990) by giving the impression that the research did not include ELs/EBs. In actuality, however, the original research conducted for this particular framework was in border areas of Texas and included many students with varying skills of word recognition and language comprehension—both in English and Spanish.

The purpose of clarifying misconceptions and erroneous claims is not to be divisive but rather to demonstrate that we are all a united field that has the opportunity to benefit from the research that exists as a basis to better understand how to support all students. This collective evidence base must continue to be built upon, and more importantly, the research that is inclusive of and specific to ELs/EBs must be paid attention to as a significant part of the science of reading. Empirical research that helps us understand the needs of underrepresented populations such as ELs/EBs, students with disabilities, students who are deaf and hard of hearing, students who speak English language variations, and students with visual impairments must be included and prioritized in national discussions and when making policy decisions.

Moving forward together: Committing to scientifically based practices is essential but not enough

The scientifically based research on reading instruction is a critical understanding that has not been historically provided to educators. It provides the knowledge that we must use to guide our instructional, curricular, and systems decisions. Currently, practices that run counter to how the brain processes print and language, such as three-cueing and leveled literacy, are still widely used in classrooms.

These fail to reliably build skills in word recognition and do not provide robust enough material to allow students to build the critical knowledge necessary to comprehend grade-level texts. These practices are preventing students from developing skilled literacy, and this is a main driver in the urgency in this movement. However, knowledge alone is not enough, and we must be humble and willing to listen to and learn from experts outside of our usual circles of information.

Whenever possible, it will be important for all within these discussions to push our collective thinking though a “yes, and” approach. We make a commitment to evidence-aligned practices and recognize the need to learn from external groups, particularly those representing historically marginalized groups of students. We must intentionally place dialogue on ELs/EBs as well as students who speak English language variations front and center in our discussions. We must build coalitions, move forward together, and create relationships that invite others in to share their opinions in an authentic, trusting, and truthful way. Together we can influence one another’s work for the better and address the challenges of misguided implementation.

The Reading League’s diversity statement includes the following language: “As a leader in our field, The Reading League is committed to furthering diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging within the science of reading movement itself, because certain communities [have] not yet seen themselves represented consistently and authentically. By calling ourselves a league, we assert that we are strengthened by the diversity of our perspectives, which will bolster our ability to advance our mission and realize our vision of literacy for all.” We have begun our first steps of reaching out to experts who work to support the needs of ELs/EBs, including representatives from the NCEL. We hope to continue to build trust and include the knowledge we have built from NCEL leaders in our materials, such as the benefits of bilingual education, the essential practice of assessing a student in their home language whenever possible, and the importance of dedicated time for English language development.

The Reading League has collaboratively built a summit along with members of NCEL to be held March 25, 2023, in Las Vegas, which will be a continuation of our purposeful discussions to build trust and find alignment. We hope these efforts will elevate the conversation that there needs to be a more intentional focus on ensuring the right of literacy for our nation’s multilingual citizens and students. We are here as a resource to reach out to before misinformation is spread to the field, and we are here to listen and learn to determine how our movement can better support the needs of ELs/EBs.

We welcome you to join us to further our understanding as we all work toward a common goal of a more literate, and biliterate, future. We are a better and stronger league when we work together.

References

August, D., Shanahan, T., and Escamilla, K. (2009). “English Language Learners: Developing literacy in second-language learners—Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth,” Journal of Literacy Research

Hoover, W. A., and Gough, P. B. (1990). “The Simple View of Reading.” Reading and Writing, 2(2), 127–160.

The Reading League. (2022). “Curriculum Evaluation Guidelines.” www.thereadingleague.org/curriculum-evaluation-guidelines

The Reading League. (2022). “Science of Reading: Defining Guide.” www.thereadingleague.org/what-is-the-science-of-reading

Kari Kurto is National Science of Reading project director at The Reading League. For more information on The Reading League Summit, visit www.thereadingleague.org/trl-summit.