Kate Kinsella offers strategies to prepare adolescent English Learners for the cultural and linguistic demands of academic interactions

The Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts (CCSS, 2010) articulate detailed grade-level expectations in the areas of reading, writing, speaking, and listening to prepare all students to be college and career ready, including English Learners (ELs). Major shifts include a focus on rigorous analysis of informational text, and evidence-based argumentation in formal presentation and writing. Equally emphasized is participation in academic discourse and collaboration with partners, as well as small and large groups. The prominent role of social interactional skills coincides with the initiative’s aim to equip secondary school graduates for a more globally networked higher education arena, workplace, and marketplace.

To meet the communication demands of the CCSS 6-12 disciplinary speaking and listening standards, students from all socio-economic and linguistic backgrounds will benefit from age-appropriate instruction in the pragmatics and language of academic and professional interaction. Every school-age youth is essentially an Academic English Language Learner (AELL), including those from professional homes in which language usage maps more readily onto classroom contexts. However, adolescent ELs and under-resourced secondary classmates will undoubtedly approach collaboration on rigorous content-based tasks with more pronounced academic oral language needs.

Limited Guidance to Support Classrooms

The CCSS introduction includes a disclaimer that delineating the instructional supports imperative for an English Learner or less proficient reader is “beyond the scope of the Standards” (CCSS, p.6). Ancillary guidelines for applying the standards in linguistically diverse and mixed-ability classrooms are available at www.corestandards.org. A few general provisions are outlined to assist limited English speakers in meeting the 6-12 English Language Arts Listening and Speaking Anchor Standard for engaging effectively “in a range of collaborative discussions with diverse partners…building on others’ ideas, and expressing their own clearly and persuasively”:

• Appropriate instructional supports to make grade-level course work comprehensible

• Additional time to complete tasks and assessments

• Opportunities for classroom interactions that develop concepts and academic language in the disciplines

• Opportunities to interact with proficient English speakers

Unfortunately, these appropriate but arguably vague instructional accommodations will be largely left to the interpretation of state, district, or school leadership. Implementation of these broad provisions for ELs will be further impacted each school site’s level of professional preparation, vision and initiative. An instructional missive to a secondary school staff serving ELs and striving readers to provide “opportunities for classroom interactions that develop concepts and academic language” is apt to be received with well-justified confusion or trepidation. Without considerable guidance in lesson design featuring complementary content and language objectives, few discipline specialists will be inspired to energize their syllabus with guided opportunities to learn with and from peers.

Hazards of Assigning “Scaffold Free” Collaborative Tasks

Secondary educators making earnest yet scaffold-free efforts to implement CCSS-aligned “collaborative conversations” are not likely to observe immediate exemplars of scholarly comportment and conceptual rigor. Pairing or grouping novice academic English speakers for productive interactions involves far more than a modified seating arrangement and a challenging depth-of-knowledge question. Classroom research demonstrates that academic talk rarely occurs without guidance and prompting during lesson discussions, whether in small group or unified class contexts (Nystrand,1997). Hastily initiated small group assignments in linguistically diverse classrooms sans step-by-step modeling and relevant academic language preparation lead to efficient yet inequitable discussions in casual English (Foster & Ohta, 2005; Gersten & Baker, 2000). Students are typically more focused on completing the basic assignment requirements in a timely manner with a modicum of effort than ensuring that every group member has competently presented ideas and received constructive feedback.

Devoid of explicit language targets and clearly communicated expectations for application, even viable cooperative structures such as Think-Pair-Share can devolve into informal neighbor chats lacking cognitive or linguistic dexterity. Similarly, assigning woefully imbalanced group roles such as the facilitator, scribe, reporter, illustrator, and encourager does little to ensure that every student engages intellectually, listens attentively, and contributes competently. With collaborative tasks designed to promote content and language attainment for ELs, each partner or group member must grapple with the focal lesson concepts and skills, ideally involving multiple language domains: speaking, listening, reading and writing. Because research on verbal engagement in the general education context and ESL classrooms alike highlights the passive observer role adopted by many ELs (Arreaga-Mayer & Perdoma-Rivera, 1996), any collaborative task must structure attentive listening and accountable verbal and written contributions from each participant.

Instructional Imperatives for Academic Interactions

To make second-language acquisition gains, adolescent ELs must have daily opportunities in every subject area to communicate using increasingly sophisticated social and academic English. Orchestrating disciplinary lesson interactions with a tandem focus on English language acceleration requires explicit instruction in the assignment goals, procedures, and relevant language tools for a myriad of communicative purposes or functions, ranging from articulating perspectives to asking for clarification (Dutro & Kinsella, 2010; Kinsella, 1996). Moreover, ELs must be required not simply encouraged to apply the target lesson language during interactive assignments, and supported by a teacher actively monitoring comprehension and language production (Saunders & Goldenberg, 2010). As an illustration, if lesson partners are asked to identify the three most significant details used to advance an author’s argument in a section of an issue-based article, a conscientious content and language mentor would pre-teach relevant skills and vocabulary for this reading standard, and provide appropriate sentence frames to guide students in accomplishing this linguistic feat: e.g., One significant detail in this section is __; Another essential detail the author includes is __. As partners grapple with identifying relevant details and voicing their perspectives, the teacher would observe student interactions, gauge both reading comprehension and language accuracy, and offer timely and productive feedback.

Proponents of problem-based or inquiry learning may argue that minimal guidance allows students to discover some or all of the concepts and skills they are expected to master. Students approaching a challenging task with conceptual voids, basic literacy skills, and an anemic command of academic language should not be routinely expected to collaboratively discover critical aspects of core curriculum they must master. Decades of research have clarified that for novices in any subject matter, explicit instruction and meticulous modeling are far more effective and efficient than limited or no guidance. Partner and group tasks can be most effective with disciplinary neophytes — not as vehicles for making conceptual and linguistic discoveries, but as a means of applying and refining recently learned content and skills (Clark, Kirschner & Sweller, 2012).

Potential English Learner Apprehensions about Collaboration

Many English Learners will not immediately embrace classroom collaboration with unalloyed enthusiasm. In fact, some are more likely to react with raised eyebrows and sighs at the prospect of a course of study infused with participation in peer working groups. There are various reasons an EL may appear apprehensive about routinely being assigned to a seemingly random group of classmates to complete critical assignments. Some recent immigrants and international students come to U.S. secondary schools and colleges with years of formative education in another country. The majority of the newcomers I have served in my ESL courses have hailed from traditional educational contexts in which instruction was habitually delivered in a teacher-fronted transmission mode. My culturally and linguistically diverse acolytes were accustomed to a highly respectful yet relatively passive learning role: listening, appreciating, recording, memorizing, and recalling. While they may have conscientiously reviewed for a test after school in the library with a classmate, they didn’t readily employ these productive collaboration skills in the classroom. Some actually voiced concerns that their American instructors were quite remiss in terms of curricular foundations and lesson preparation as they routinely relied upon small-group learning to address lesson objectives rather than informed, organized, and direct instruction. In essence, they viewed some instructors in their new school system as pedagogical slackers not cutting edge constructivists.

The scores of U.S.-educated language minority students I have interacted with in classes and projects articulate additional reasons for their group-work angst. A recurring complaint from reticent collaborators is the lack of procedural modeling, linguistic preparation, and in-process monitoring and support they receive to accomplish assigned tasks across the subject areas. Embarking upon a hastily-defined and preparation-free assignment with three hapless peers invariably results in a less than laudable outcome. In one predictable scenario, perplexed collaborators remain in a state of inertia after perusing the assigned exercise. After an uncomfortable silence, the most industrious scholar resorts to completing the task independently while others observe passively. The lone group member who actually reflected and penned ideas thus becomes the default scribe and reporter. Convincing culturally and linguistically diverse students with a track record of similar uneventful or negative classroom collaboration that four heads are actually better than one requires more than lip service testimonials about inquiry-based learning.

Gathering Student Input on Classroom Work Style Preferences

Obtaining input on students perceived classroom work style strengths and prior educational experiences with learning groups is a valuable preliminary step in helping skeptical adolescent collaborators. Without some working knowledge of students’ preferences and biases regarding assignment completion, it is difficult for secondary educators to anticipate potential pitfalls and offer a compelling pedagogical rationale. I utilize two efficient tools to gain insights into my second-language students’ classroom collaboration narrative, while simultaneously engaging them in metacognition, constructed writing, and provocative academic discussion.

After reviewing my Academic English course objectives, I acknowledge that active participation in varied classroom learning formats is a priority. Since my primary responsibility is to advance their spoken and written English proficiency for academic success, I will structure ample lesson opportunities for students to interact with a partner or a group to maximize verbal engagement.

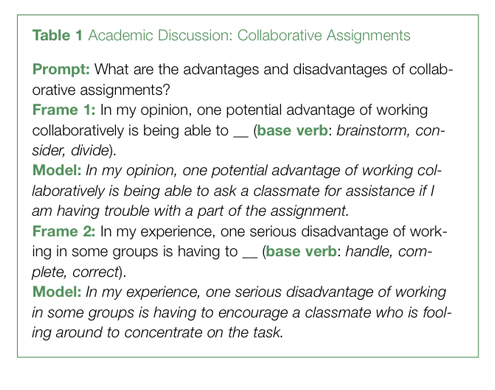

My initial assessment tool (See Table 1) is a brief academic writing and discussion prompt: What are the advantages and disadvantages of collaborative assignments? I preface the prompt by acknowledging that as a student and colleague, I have certainly experienced group assignments that were wonderfully memorable and stimulating as well as regrettable and unproductive. My aim as their second-language mentor is to structure promising and purposeful classroom collaboration that enhances their content knowledge and English proficiency while equipping them with skills that will serve them well in school and work contexts. To support students in constructing competent verbal and written responses, I provide sentence frames with model responses and clarify the grammatical target. Once students have completed their written observations, I ask them to pair up with an “elbow partner” to voice attributes and drawbacks using the sentence frames. This guided academic interaction enables ELs to rehearse and refine ideas before the subsequent unified-class discussion. Documenting and displaying their contributions validates students’ experiences while encouraging them to entertain diverse points of view. Moreover, this collective content serves as a springboard for my avowal to craft group assignments are at once clear, purposeful, interactive, and accountable, allowing them to reap the purported benefits of collaboration.

Another productive vehicle for obtaining input about students’ work style preferences is the Classroom Work Style Survey (Kinsella, 2006) downloadable at www.languagemagazine.com. I developed this classroom research instrument to offer my linguistically diverse secondary students a nonthreatening opportunity to articulate some of their general working habits and inclinations. After analyzing the class data, it is quite apparent which students have particularly strong biases in favor of completing lesson tasks independently, with a partner, or with a group. The survey also sheds light on the students’ preferences with regard to selection and assignment of fellow collaborators.

Administering this survey to numerous classes, I have identified a number of trends as well as surprises. A consistent finding, whether I am teaching relative newcomers or long-term U.S. residents, is that adolescent ELs appreciate having opportunities to work with a single partner more frequently than a group, if given the option. I share their perspective that many collaborative tasks in a language development class are more efficiently accomplished in a productive duo. By initially structuring task-based interactions with single partners, I can build both skills and credibility for the process that can be leveraged later in small groups. Another insight I have gleaned from U.S.-educated bilinguals is that most actually prefer to have their instructor establish heterogeneous working groups. The common reasons are that they want to meet students from different backgrounds, practice English, and stay focused on the task, but don’t want to run the risk of alienating their historical friends if they opt to work with classmates from another community. On the contrary, I have found that students in early stages of English-language acquisition would generally rather collaborate initially with familiar classmates from the same cultural background so they can rely on their primary language to solicit clarification or assistance.

Regardless of their level of English proficiency or cultural background, students appreciate hearing the highlights of the class survey. I display the most salient findings and emphasize that I will take their feedback into careful consideration when designing interactive lessons and assigning collaborators. Students appear relieved and delighted to learn that some, if not a majority of, their classmates shared work style preferences, and that their teacher is poised to strike a reasonable balance between independent, partner, and group tasks to help them become more flexible scholars and valued colleagues.

Providing a Compelling Rationale for Classroom Collaboration

Adolescents approaching partner and group tasks with limited or uninspiring experiences will need a compelling rationale for collaboration within and beyond U.S. secondary school coursework. Students boasting an impressive academic track record, largely achieved independently, warrant the most informed and eloquent defense. Simply displaying the Common Core State Standards emphasis on “opportunities for classroom discourse and interaction” is not apt to make self-directed academicians do a collaborative 360-degree about face.

First and foremost, educators across the disciplines must point out the pivotal role academic interaction and productive task-based learning will play in their respective courses. Since the national standards for listening and speaking call for cross-curricular initiatives to develop students’ communicative strengths, it cannot be incumbent upon the ESL teacher or English Language Arts teacher to assume the lion’s share of responsibility for addressing the pragmatics and language skills for advanced academic discourse. ELs who hear consistent messages throughout the school day about the utility of collaborative skills, coupled with a host of carefully-orchestrated experiences, are far more likely to let down their defenses and ultimately participate on equal footing with native English-speaking classmates.

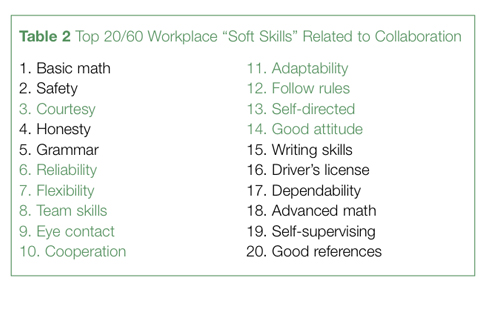

In recent demonstration lessons for secondary school ELs, I have made great inroads with skeptics and fragile collaborators alike by sharing data from the Workforce Profile, an assessment of high priority skills sought by a wide spectrum of U.S. businesses and industries in new employees (available at www.workforce.com). According to the survey results, the employees most valued by CEOs and human resource directors are those who display a variety of “soft skills,” enabling them to grow and learn as the work environment changes. “Soft skills” are personality traits and abilities such as courtesy and flexibility deemed as important, if not more vital, than traditional technical skills such as facility with creating spreadsheets or operating a particular type of machinery. It is important to point out that at least ten out of the top twenty soft skills are directly related to success in classroom collaboration, from eye contact to cooperation (See highlighted skills in Table 2).

Introducing the 4 Ls of Productive Partnering

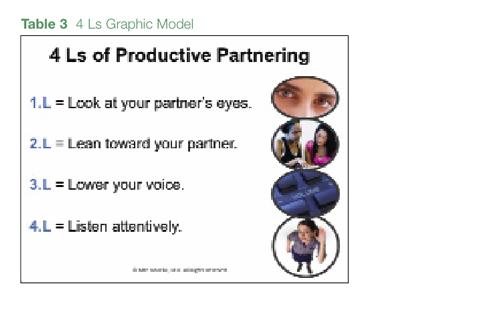

Since my linguistically and culturally diverse classes have consistently voiced a preference for regular partner tasks and occasional group work, I design structured partner interactions in every lesson for the first quarter. As a means of initiating language minority students to the soft skills of academic interaction, I recommend enhancing your collaboration campaign by introducing the “4 Ls of Productive Partnering.” If students learn the body language and communication skills of a productive partner, they will be well primed to segue to small group tasks.

1. Begin by prominently displaying a visual highlighting the “4 Ls for Productive Partnering” (See Table 3 for an illustration).

2. Establish a rationale for partnering in your lessons. For example: My goal is to help prepare you for the communication demands of secondary school, college, the workplace, and formal contexts like speaking to a job interviewer, bank manager, or police officer. Knowing how to interact with a classmate, coworker, supervisor or professor is essential to academic and professional success. When you are communicating with a work partner at school or on the job, it is important to observe the “4 Ls of productive partnering.”

3. Model how to do each of the “4 Ls” using a student as your partner. Accompany your modeling with clear and compelling justification. Use the sample language provided to craft an appropriate rationale for each “L.”

• Look at your partner’s eyes: In North America, eye contact signifies respect and active listening when two people are interacting. Maintaining eye contact indicates “I am paying attention to you.” Looking directly at the other speaker is critical at school, work, church, and other formal social contexts. Looking away or fiddling with something can readily signal that you are distracted or disinterested. That isn’t universal; in some cultures, eye contact may either be unnecessary or a sign of disrespect if a child looks directly at an adult. In the U.S. workplace, eye contact is viewed by employers in many different industries and businesses as one of the top ten “soft skills” they seek in new employees (Point out the Workplace “Soft Skills”).

• Lean toward your partner: Like eye contact, leaning toward someone during a formal interaction indicates you are focused on what they are saying and not paying attention to other people or things. Just as you lean forward to focus a camera to take a close-up picture of a person, leaning toward your partner shows that you are trying to pay careful attention to his/her ideas. On the other hand, leaning back communicates that you could be bored, disinterested, or in disagreement with what your partner has just stated.

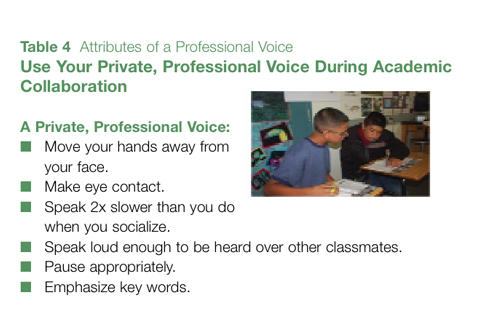

• Lower your voice: Use a private, professional voice when interacting with a partner at school or work. Speak loudly and slowly enough with emphasis for your partner to easily hear and comprehend what you are saying, but not so loud that you are distracting or interrupting anyone nearby. Never whisper to your partner. Whispering is for secrets and gossip. If you speak too softly, your partner will not be able to hear and remember what you are communicating. In college and the workplace, a soft, inaudible response during a group discussion is viewed as a lack of confidence and preparation. (See Table 4 for the attributes of a private, professional voice.)

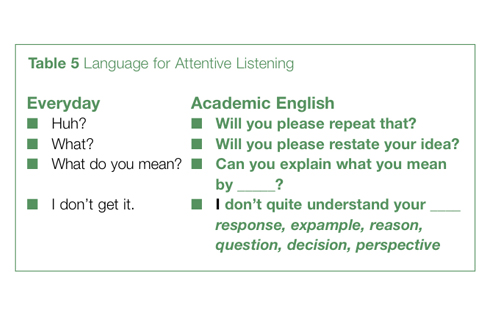

• Listen attentively to your partner: Your responsibility is to not only share your perspective and contribute equally, but also understand and remember your classmate’s idea. (See Table 5, Language for Attentive Listening). If a close friend is showing you how to play a new video game but going too quickly, it is absolutely appropriate to say “What? Slow down.” In school or the workplace, saying “Huh? I don’t get it.” would be viewed as very causal and impolite. If you were not able to catch what your partner said, ask him/her to repeat or restate the idea. If you don’t quite understand the idea, ask him/her to explain it in more detail. To make sure you have truly grasped the idea, repeat it using your own words. This shows that you care enough to get the idea right. You should understand your partner’s contribution well enough to be able to report it confidently to the class.

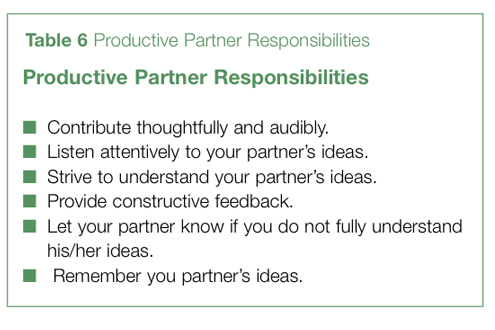

4. Conclude by reviewing the responsibilities of productive partners in lesson collaboration (See Table 6, Productive Partner Responsibilities).

Addressing the Language of Classroom Collaboration

Despite the complexities of daily classroom communication, all too frequently secondary students are placed into an interactive learning format without having been prepared for the linguistic demands of the task. English language development scholars (Dutro & Kinsella, 2010) and cooperative learning aficionados (Kagan, 1992) equally emphasize the importance of formally teaching native English speakers and ELs the language functions they need to successfully achieve an array of classroom communicative purposes. While content area colleagues may take time to pre-teach critical disciplinary concepts before launching an applied collaborative task, the nuts and bolts of facilitating a discussion, synthesizing group ideas, or politely disagreeing are left to chance. Like other aspects of complex curriculum, interactive language tools are best acquired in manageable, timely doses, with explicit guidance and modeling, rather than solely through self-discovery.

Over the course of a semester, I plan my units of study to include increasingly complex partner and group tasks, often revisiting a vital language function like clarifying contributions with more sophisticated phrasing. On day one, I introduce the 4 Ls of productive partnering in tandem with language for attentive listening. This initial lesson helps lay foundational linguistic groundwork, establishing register distinctions between casual or everyday English and academic English. I want them to recognize that it is entirely appropriate to tell a close friend or trusted colleague “Huh? I don’t get it,” while emphasizing what a negative impact that phrasing is likely to have on a prospective employer, financial aid officer, or college professor. I also want students to grasp their fundamental responsibility to lesson partners — to strive to truly understand what their fellow collaborators are communicating and provide constructive feedback. I point out that if you missed important information or didn’t understand your partner’s contribution, you must ask for clarification or repetition, but never sit idle and passive, indirectly conveying indifference. When pressed to report a partner’s idea, many unsuspecting and inattentive classmates have sheepishly conceded “I forgot,” “I’m not sure,” or “He never said anything.” In a technical training, university seminar, or department meeting, this collegial disregard would be viewed quite negatively.

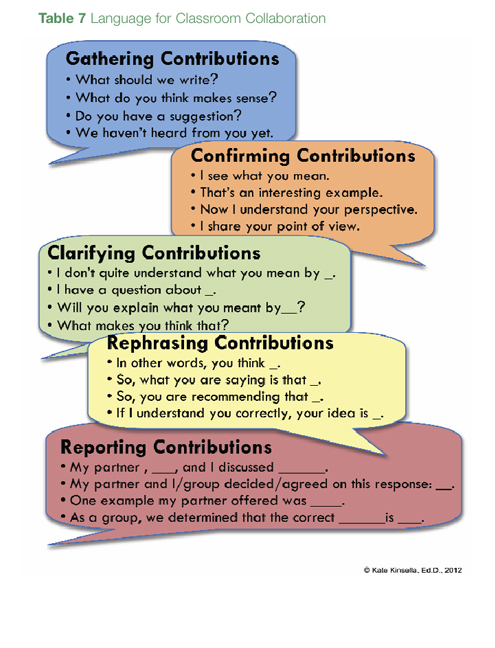

Recognizing how linguistically ill-equipped my nascent collaborators tend to be, I have prepared a relevant starter package to assist them with fundamentals of academic and professional team work. Working one-on-one with a lesson partner necessitates language for gathering, confirming, clarifying, rephrasing, and reporting contributions (See Table 7, Language for Classroom Collaboration). To ease them into group work, I initially hold them responsible for productively interacting with just one classmate in an array of structured tasks over the course of a unit of study. As I assign their initial task, I address the importance of showing interest and respect for others’ ideas by conscientiously gathering contributions. I model how to productively solicit input from a lesson partner or colleague by appearing genuinely interested and asking “What do you think makes sense?” or “Do you have a suggestion?” I subsequently direct partner 1 to ask partner 2 to demonstrate authentic interest in partner 2’s perspectives and ask a relevant question. In subsequent lessons, I introduce language for confirming and clarifying contributions so that by week’s end, students not only recognize the importance of clearly communicating their own observations and perspectives but also soliciting, comprehending, and remembering their partner’s contributions.

Concluding Remarks

As we strive to implement new standards with a focus on career and college readiness, inter-disciplinary colleagues will have dual responsibilities to address complex subject matter standards while integrating opportunities for diverse learners to flex their language muscles engaging in productive academic interactions. Imagine the collective impact a school staff can have on under-resourced scholars and ELs if we each entered the classroom daily, conveying the enthusiasm for our field of study and linguistic acumen that originally propelled us into the teaching profession.

References

Clark, R.E., Kirschner, P.A., & Sweller, J. (Spring 2012). “Putting students on the path to learning.” American Educator, 6-11.

Common Core State Standards Initiative (2010). Common Core State Standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Retrieved from www.corestandards.org/assets/CCSSI_ELA%20Standards.pdf

Dutro, S., & Kinsella, K. (2010). “English language development: Issues and implementation in grades 6-12” in Improving education for English learners: Research-based approaches. California Department of Education.

Foster, P., & Ohta, A. 2005. “Negotiation for meaning and peer assistance in second language classrooms.” Applied Linguistics, 26(3), 402-430.

Gersten, R., & Baker, S. (2000). “What we know about effective instructional practices for English-language learners.” Exceptional Children, 66(4), 454-470.

Kagan, S. (1992). Cooperative learning. Kagan Cooperative Learning.

Kinsella, K. (1996). “Designing group work that supports and enhances diverse classroom work styles.” TESOL Journal, 6(1), 24-30.

Nystrand, M. (1997). Opening dialogue: Understanding the dynamics of language and learning in the English classroom. New York: Teachers College Press.

Saunders, B., & Goldenberg, C. (2010). “Research to guide English language instruction” in Improving education for English learners: Research-based approaches. California Department of Education.

Kate Kinsella, Ed.D. (katek@sfsu.edu) is an adjunct faculty member in San Francisco State University’s Center for Teacher Efficacy. She provides consultancy to state departments of education throughout the U.S., school districts, and publishers on evidence-based instructional principles and practices to accelerate academic English acquisition for language-minority youths. Her professional development institutes, publications and instructional programs focus on career and college readiness for ELs, with an emphasis on academic language and high-utility vocabulary development, informational text reading, and writing.