Throughout IDRA’s almost five decades, we have paid close attention to how we speak about people in terms of race or ethnicity, gender, etc. Words matter.

Almost 5 million students in U.S. public schools are learning English as a second language. That’s over 10% of the student population. The number almost doubled over the last 15 years. IDRA recently took another look at the terminology used to identify these students and the implications of using certain labels.

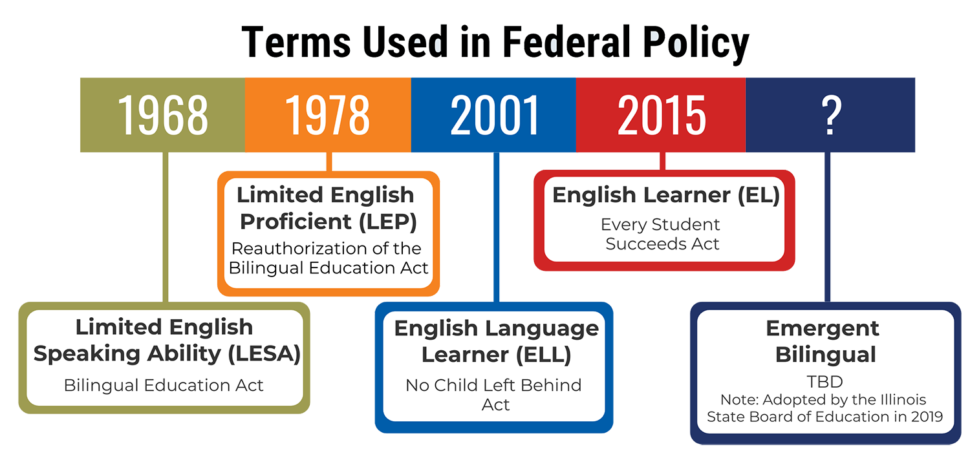

Most state policies refer to students with a first language other than English as English learners or English language learners, while 10, including Texas, use some form of limited English proficient students (LEP).* The Texas Education Agency also uses English learners in documents. At first glance, these labels may seem neutral and plainly descriptive; however a closer inspection reveals that these terms are deficit-based, that is, they define students by the knowledge they lack, rather than the strengths and abilities they already bring into the classroom.

Such terms can affect how we understand students and their potential. They can cause us to give English more legitimacy and power than a student’s first language. Additionally, because of the language used to define students, many may see them as a needy, expensive to educate, monolithic group, rather than a diverse group of students who represent a necessary resource and asset.

In Texas, for example, almost one in five students are designated English learners. Labeling almost 20% of Texas students as limited English proficient students or English learners can negatively affect how policymakers and educators measure those students’ potential. It starts with a deficit understanding of their abilities, labels them in terms of a cost that schools struggle to afford, funnels them into particular pathways according to perceptions, and often limits their access to critical learning opportunities, such as college-level coursework (Martinez, 2018). Because emergent bilingual students are seldom viewed as college material, only one in 10 are deemed college ready at graduation (TEA, 2018).

IDRA believes in the value of bilingualism and biculturalism. Schools must protect the civil rights of all students by preserving and celebrating the cultures and experiences tied to the diverse languages students bring into the classroom. For these reasons, IDRA prefers using the term emergent bilingual students.

Coined and popularized by Dr. Ofelia García in 2008, emergent bilingual focuses on the unique potential for bilingualism possessed by students who are learning English in school. This terminology demands that we take an asset-based view of the capabilities of emergent bilingual students, who are simultaneously acquiring a new set of linguistic capabilities in school and building on the valuable knowledge of their first language.

By adopting the emergent bilingual distinction, we hope that education stakeholders at all levels begin to imagine classrooms where linguistic diversity is praised rather than shunned, and where students are intentionally invited to leverage their full linguistic and social repertoire in all learning environments (Ascenzi-Moreno, 2017). To propel this change, IDRA also is working with state lawmakers and education agencies, school districts and community members to encourage the use of the term emergent bilingual in state law, administrative codes and at the school level.

* In some regions of the country, the term “dual language” learner is used, which can be confused with the instructional program that is also called “dual language.”

Resources

Ascenzi-Moreno, L. (Fall 2017). From Deficit to Diversity: How Teachers of Recently Arrived Emergent Bilinguals Negotiate Ideological and Pedagogical Change.Schools: Studies in Education, Vol. 14, No. 2.

City University of New York. (2019). Vision statement – Emergent Bilinguals: Emergence, Dynamic Bilingualism, and Dynamic Development. CUNY-New York State Initiative on Emergent Bilinguals.

Education Commission of the States. (2020). 50-State Comparison: English Learner Policies – How is “English learner” defined in state policy? webpage.

García, O., Kleifgen, J.A., & Falchi, L. (2008). From English Language Learners to Emergent Bilinguals. Equity Matters: Research Review, No. 1.

Martínez, R.A. (2018). Beyond the “English Learner” Label: Recognizing the Richness of Bi/Multilingual Students’ Linguistic Repertoires. The Reading Teacher.

Rosetta Stone. (2020). Emergent Bilinguals Are the Future. Rosetta Stone.

Texas Education Agency. (2020). 2020 Comprehensive Biennial Report on Texas Public Schools. Austin, Texas: TEA.

Araceli García is an IDRA Education Policy Fellow. Comments and questions may be directed to her via email at [email protected].

[©2021, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the February 2021 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]