“The notion of ‘multiliteracies’ describes the suite of essential skills students should possess in this globalized and digital age.”

Significance of Multiliteracies

Today’s K–12 classrooms are brimming with the use of technology. Students use computers and websites to access digital materials, work on projects and produce presentation materials, and take assessments, to cite a few examples. Alongside this widespread technological adoption, the growing linguistic and cultural diversity in classrooms has broadened the essential literacy skills required for students. Literacy skills extend beyond reading and writing printed texts and increasingly involve navigating varied communication styles in diverse contexts.

The notion of “multiliteracies” more aptly describes the suite of essential skills students should possess in this globalized and digital age. Multiliteracies emphasize two main facets of language use: The first relates to various meaning-making patterns in different social and cultural contexts. The second has to do with multimodality—with the advancement of technology, where the written mode of meaning interfaces with various modes of meaning including audio, gestural, oral, spatial, tactile, and visual (Cope and Kalantzis, 2015).

In fact, multiliteracies have already been integrated into current academic standards designed to prepare all students for college and careers. Let’s take a sixth-grade reading standard for informational text as an example: “Integrate information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively) as well as in words to develop a coherent understanding of a topic or issue” (Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2010, p. 39). This standard explicitly calls for students to demonstrate understanding and to integrate meanings from multiple formats and channels.

The concept of multiliteracies also resonates in writing standards. For instance, a seventh-grade writing standard states: “Use technology, including the Internet, to produce and publish writing and link to and cite sources as well as to interact and collaborate with others, including linking to and citing sources” (Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2010, p. 43).

Aside from technological literacy, the anticipation of interacting and collaborating with others in writing underscores the students’ ability to navigate different patterns of communication in culturally and linguistically diverse classrooms.

Using an Assessment Strategy to Support Multilingual Learners

Clearly, the language and literacy skills expected of today’s students are rigorous and sophisticated. These multiliteracies are important for college and career preparedness as well as 21st-century readiness. So, how can we ensure that multilingual learners (also known as English learners) meet these standards that require multiliteracies? Since multilingual learners already possess a repertoire of diverse communication codes, how can we enhance their multilingual assets while aiding their development of multiliteracies? Before delving into these questions, it is worth clarifying the term multilingual learners, which we use in place of English learners. The latter term is defined by federal statute as students whose language at home is not English and whose English proficiency is still developing, hindering meaningful participation in English-speaking classrooms.

While not all multilingual learners require the language support mandated by law, a subset of this student population is specifically referred to as English learners. Our choice of multilingual learners adopts an asset-based perspective that values their rich linguistic diversity and funds of knowledge.

In effective teaching and learning, assessment plays a pivotal role in identifying students’ strengths and weaknesses relative to learning goals. However, existing assessments, especially standardized ones in content areas, frequently face criticism regarding their validity and utility for multilingual learners. Teachers report that some of their multilingual students disengage during assessments due to language barriers. They also express concerns about how assessment results often provide little useful information beyond simply indicating that students have not achieved proficiency.

In our R&D project, our goal was to develop a research-based assessment tool specifically designed to meet multilingual students’ needs. We envisioned that this assessment tool would be used for formative purposes, as a classroom-based assessment and instructional resource to help students improve multiliteracy skills.

Moreover, our aim was to design a tool that would foster greater student engagement in assessments, all while maintaining the rigor of grade-level academic standards and the targeted skills to be measured. Our efforts were also focused on creating an assessment that serves as a valuable learning activity, allowing students to learn as they engage with the assessment process (i.e., assessment as learning).

Socioculturally Responsive Assessment to Facilitate Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy

To design our assessment tool in alignment with the aforementioned goals, we adopted the principles of socioculturally responsive assessment and culturally sustaining pedagogy as our guiding frameworks. Paris (2012) introduced the term culturally sustaining pedagogy to emphasize the importance of schooling that nurtures and bolsters multilingualism and multiculturalism in a pluralistic society.

He asserts that “our pedagogies should be more than responsive of, or relevant to, the cultural experiences and practices of young people—it requires that they support young people in sustaining the cultural and linguistic competencies of their communities while simultaneously offering access to dominant cultural competence” (Paris, 2012, p. 95).

This concept offers a useful framework for teachers to discuss and plan instruction for multilingual learners. To effectively practice this pedagogy, a new assessment design is necessary. In reckoning with the criticism of standardized assessments that often neglect the diverse backgrounds of students in assessment design, Bennett (2023) proposed five design principles to make assessments more socioculturally responsive (see Table 1).

Table 1. Bennett’s (2023) Design Principles of Socioculturally Responsive Assessment

| Principle 1 | Present problem situations that connect to, and value, examinee experience, culture, and identity |

| Principle 2 | Allow for multiple forms of representation and expression in problem stimuli and in responses |

| Principle 3 | Promote instruction for deeper learning through assessment design |

| Principle 4 | Adapt the assessment to student characteristics |

| Principle 5 | Represent assessment results as an interaction among what the examinee brings to the assessment; the types of tasks engaged; and the conditions and context of that engagement |

These principles are particularly beneficial for assessing multilingual learners. These students may be better able to demonstrate their knowledge and skills when presented with contexts related to their cultures or when assessment content is tailored to accommodate their English proficiency levels.

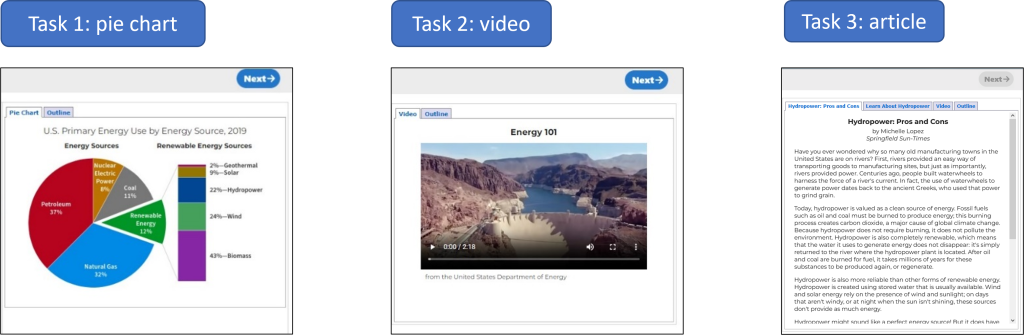

Figure 1. Diverse sources included in the assessments of multiliteracies

Main Assessment Features

What features might enable multilingual learners to engage fully with the assessment content and thereby to be able to better demonstrate their reading and multiliteracy skills? To answer this question using socioculturally responsive assessment principles, we embarked on a co-design effort, designing new assessment features collaboratively with educators of multilingual learners. We started with an existing online interactive assessment developed by ETS in which students build and share knowledge about informational texts related to hydropower.

The existing assessment contained multimodal information for students to learn from and to communicate about, with a focus on assessing multiliteracies. As displayed in Figure 1, the assessment consisted of a pie chart, a video, and an article on the topic of hydropower as a renewable energy source. A set of questions was included for each source of information.

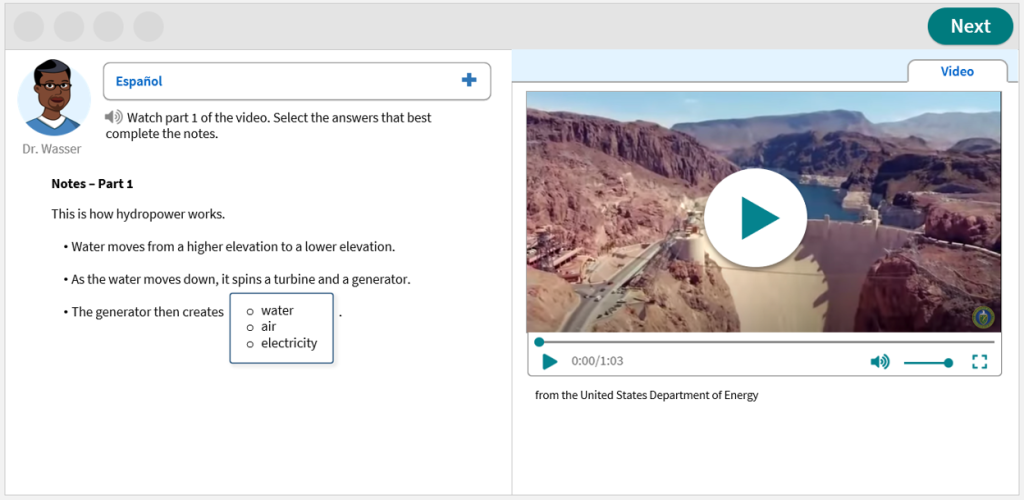

Figure 2. Example of Form 1 task, guided notes

Our discussions with teachers led to the inclusion of the following additional design features, based on socioculturally responsive assessment principles: (1) leveled texts, (2) linguistic and multilingual supports, and (3) scaffolding for comprehension.

Leveled Texts

“Let’s meet multilingual learners where they are”—in other words, adapting the assessment to multilingual learners’ characteristics—was a mantra of the project team. Multilingual learners have varying levels of English proficiency. To access academic texts in English, they require individualized support. Furthermore, classrooms increasingly comprise multilingual learners at different English proficiency levels.

One way to help ensure students in mixed-level classes engage in learning about the same grade-level topic is to provide leveled texts that match students’ English-language proficiencies. With this premise, we created three separate forms of the assessment—for multilingual learners at advanced (form three), at intermediate to advanced (form two), and at high-emerging to low-intermediate (form one) English proficiency levels—to ensure multilingual learners within a single class could engage in the same topic and be measured on the same English language arts and English-language proficiency standards. Whereas form one featured cognitively rigorous but linguistically modified texts, form two featured “amplified” texts (Walqui and Bunch, 2019); that is, the multimodal texts were enhanced or enriched instead of simplified. (Examples of those enhancements are described in the next sections.) Texts in forms two and three were otherwise the same.

Linguistic and Multilingual Supports

Providing appropriate language supports in the moment can allow multilingual learners greater access to academic content in English and may ultimately help them to better demonstrate their reading and multiliteracy skills. In the assessment, these supports include, for example, closed captioning for videos, glossaries, supportive visuals that clearly illustrate key points in the texts, choice of language for directions (e.g., English or Spanish), and choice of audio or written format for directions. We provided multilingual directions in both audio and written formats following an asset-based approach, as a means of enabling multilingual learners to leverage their full range of language skills for learning and assessment. And we offered students choices in language and format to provide flexibility and in consideration of students’ needs and preferences. With the inclusion of these supports, we hoped that students would use their multilingual assets to learn more deeply about the topic of hydropower and thereby be better equipped to show what they had learned.

Embedded Scaffolding

A final example of adapting the assessment to multilingual learners’ characteristics is the scaffolding embedded within the assessment activities. To illustrate one example, the video content was chunked into three parts.

We also embedded guided notes for each part (Figure 2) to alleviate the language demand while providing a note-taking strategy to help comprehension. Multilingual learners taking form two filled in guided notes with sentence frames, and those taking form one selected from multiple-choice options to complete sentences. This kind of scaffolding offers multilingual learners written support (i.e., the guided notes) for a multimodal text (i.e., the video) at a linguistic complexity appropriate to their English proficiency level. Our goal in embedding scaffolding within the assessment activities was to provide in-the-moment support to multilingual learners at a range of English-language levels so they would be able to access and engage in learning about the rigorous informational content in the assessment.

What Did Teachers Say about Our Approach?

We conducted a small-scale usability study with four English learner teachers and their students. The teachers shared their experiences and perceptions of our assessment approach after trying it out with their multilingual students. We share a few notable findings along with teachers’ feedback and comments.

Teachers used the assessment and design features strategically to engage multilingual learners and facilitate their participation in classroom assessment tasks. As with any educational material, the teachers reported adapting the use of the assessment based on the specific characteristics or needs of their students. For instance, one teacher commented that a majority of her class was reading below grade level and needed additional support to engage with the assessment content. She began her lesson with a warm-up activity to activate students’ background knowledge about the topic and introduced new vocabulary before having students work on the assessment. Then, the teacher assigned different forms of the assessment to students based on their English proficiency levels. Notably, all four teachers utilized two to three different assessment forms to accommodate their students’ varying levels and assess their literacy skills.

How Teachers Saw Multilingual Learners Use the Embedded Supports

Overall, the teachers were in favor of the embedded supports, stating that they catered to the types of assistance multilingual learners need, and considered that these supports facilitated student engagement with the assessment content. One teacher highlighted that the translation and visual images helped multilingual learners understand that they could leverage all their meaning-making resources. Furthermore, these supports reinforced the idea that using languages other than English is an acceptable way to develop their literacy skills. The multilingual directions were also instrumental in helping students comprehend the instructions and decipher unknown words. All the teachers conveyed a wish to have the translation feature in several languages, not just Spanish, to accommodate students’ diverse home languages.

Additionally, the read-aloud feature was found to be beneficial in aiding students in pronouncing difficult words, as well as assisting those who struggled to read the articles independently in understanding the content. Another teacher pointed out that the video captions were particularly useful for her emerging-level students, as they facilitated a better grasp of the video content.

Teachers commented that having multiple levels (or forms) of the assessment allowed all their students to work on the same set of skills using the same topic in the assessment. They uniformly praised this feature, noting that it provided an opportunity for all students to engage with the same rigorous content. One teacher remarked, “The three levels did an excellent job of identifying my students’ strengths and areas for improvement. I can’t think of anyone who wouldn’t be captured by one of those three levels.” Teachers also appreciated the various forms of representation (i.e., graphs, videos, and articles) along with the multiple embedded supports. As one teacher put it, “This approach allowed me to discern which students could perform which skills in which contexts.” These teachers’ perceptions and comments resonate well with the principles of socioculturally responsive assessment, wherein assessment information should be interpreted based on the interaction between students’ characteristics and the context of the assessment.

Concluding Thoughts

Through our work, we explored the potential of assessing multilingual students’ reading and multiliteracy skills by leveraging the principles of socioculturally responsive assessment.

We illustrated a concrete example of our assessment design and shared feedback from teachers regarding our approach. To support culturally sustaining pedagogy that recognizes and embraces the diverse characteristics of all students, new thinking and approaches to assessment design are necessary. The principles of socioculturally responsive assessment herald a paradigm shift from rigid standardization in assessments toward flexibility and adaptability, thereby empowering both individual learners and educators. We hope that these efforts will spur further innovative ideas for more effectively assessing multilingual learners and supporting their development of critical literacy skills.

References

Bennett, R. E. (2023). “Toward a Theory of Socioculturally Responsive Assessment.” Educational Assessment, 28, 2, 83–104.

Common Core State Standards Initiative (2010). Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/ Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects.

Cope, W., and Kalantzis, M. (2015). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Learning by Design. Palgrave.

Paris, D. (2012). “Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice.” Educational Researcher, 41, 3, 93–97.

Walqui, A., and Bunch, G. C. (Eds.). (2019). Amplifying the Curriculum: Designing Quality Learning Opportunities for English Learners. Teachers College Press.

Lorraine Sova is an assessment specialist at ETS focused on developing English language assessments for young learners as well as teaching and learning content for English language educators and students. Dr. Sova has particular interests in second language learning and literacy in diverse young learner classrooms.

Mikyung Kim Wolf is a principal research scientist at ETS. She has over 20 years of experience in developing and researching language assessments for multilingual learners. She has edited two books on language assessments: Assessing English Language Proficiency In U.S. K-12 Schools (2020, Routledge) and English Language Proficiency Assessment for Young Learners (2017, Routledge).

Alexis A. López is a Senior Research Scientist at ETS. He earned a Ph.D. in Education and an M.A. in TESL from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His research focuses on assessing the language proficiency and content knowledge of K-12 multilingual learners.

The authors would like to acknowledge their project team, including Ellen Gluck, Reginald Gooch, Gerriet Janssen, Jeremy Lee, and Emilie Pooler, for their valuable contributions to the project. They also extend gratitude to the teachers and students for their active participation in and collaboration on the project.